Work Cultures

I had never worked outside of the United States until July of this year, when I moved to Korea. I've never really discussed how the whole thing came about, because Korea has notoriously prickly rules and laws about disclosure, and until I know the consequences, I probably won't ever post about which company is currently employing me. However, I have no problem talking about my situation and my observations, and how I came to be in Korea.

I have no qualms about telling someone that I am good at my job. I've been working in this industry since May of 2003 (working in post-production on various projects). Since April of 2005, I have worked exclusively in post-production- specifically, visual effects- on films. In the years that I've spent working on movie after movie, I've learned, I've adapted, and I've generally become better at my job. After two movies, I was competent. After four movies, I was good. Now, I'm efficient, I know what to do and how to do it well, and I'm an asset to the producer for whom I am working. This may all sound conceited, but I promise that I have self-esteem issues, like most of the world's population, and one of the few areas in which I am truly confident is my work.

Anyways. In 2005, I met an artist during my first movie ever ("The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch, & The Wardrobe"). We weren't really friends, we were just co-workers, and we sort of became acquaintances because we were on the same team at work. I worked with him again a time or two before I left that company and moved on.

Fast-forward to early 2011, when I'm in Albuquerque, working on "The Green Lantern" and wondering what I should do next, knowing that I want to leave New Mexico and not having much of a plan (which is quite liberating, let me say). Suddenly, whaddya know, that artist calls me up and asks me if I'd ever consider working in Korea.

Well. It's as if the stars aligned or something, because haven't I been going on and on about how I wanted to try living in Korea? Yes, I have. So after a couple months of sporadic e-mailing and a few phone calls at weird hours with this company, I found myself with gainful employment in the motherland, not knowing a soul that works at the company I've agreed to enter. (Side note: I would have gone about the process much differently if I didn't know the person that had introduced me to the company. Don't get sucked into one of those schemes aimed at foreigners!)

What with the vacationing through New Mexico, the move back to LA, and the vacation to the Caribbean, all in June, I didn't really have time to let myself get worried or anxious about relocating to a whole different country. I didn't even pack to move to Korea until the day before my flight. I was so busy meeting friends, saying goodbyes, and having coffee with my parents that I forgot that moving to a country 6,000 miles away from my home was kind of a big deal.

As it turns out, I'm really glad that I didn't worry. Because as it really turns out, moving far from home is only as big a deal as you make of it. Late at night on July 4, my sister drove me to the airport as we watched fireworks on either side of the 105. I checked in, went through security, and sat at my gate, charging my phone and my iPad while I sent texts for the last time, before my phone service shut off (actually, it's suspended until I get back).

Moving to Korea and living here isn't as momentous a change as I had thought it would be. I don't wake up in the morning and think, "I'M IN KOREA," I just wake up and think, "I want another couple hours of sleep." Despite the language and the obvious appearance of the people here, it doesn't occur to me very often that oh, my gosh, I'm in Korea.

I can say all this now because it's been about two and a half months since I started working, and I have (finally) gotten used to the changes in my life. I don't think that 2.5 months is that long of a time, though- even when I moved to Albuquerque, I had quite a long adjustment period. (Koreans were easier for me to adapt to than Albuquerquians, actually- though that's a whole separate post.)

Since I've got some time under my belt and am feeling quite a bit more comfortable here, I thought I would put together my thoughts on how different the work cultures are between Korea and America. Mind you, I work in a weird industry, so this doesn't hold true (AT ALL) for people with other types of jobs (investment bankers, this is not for you).

- Automatic respect:

Koreans use two different types of speech (and writing): casual and formal. (There's actually an uber formal type, as well, but let's disregard that for the sake of this discussion, as it's used only very rarely.) If you've just met someone for the first time? Formal (unless that someone is a child). If someone is older than you and you're not super close? Formal. If someone is the same age as you and you're friends? Casual. If someone is younger than you and also lower on the food chain than you? Casual. If you are quite high on the totem pole, even if you're not the oldest? Casual (the CEO of the company, who isn't the oldest person at work, speaks casually to everyone, as far as I can tell- he speaks to me in English, so we're both casual). I drop my speech every now and again to the kiddies (people in their early twenties) at work, and they don't even blink an eye, because I'm older (and foreign).

Americans, especially people in LA, have one type of speech: casual. Super casual, on occasion, and very often laced with curse words that are just part of the conversation, not necessarily expressions of anger. This levels out the playing field, I think. Whether you are the PA or the director, everyone speaks to you in the same way. The PA does not call the director by his title. There are titles galore in Korea. And sometimes, one person has more than one title. I had a tough time with this, as some of the supervisors are also directors (or general managers) of the company (감독님 vs. 본부장님). I now know the difference, and use the titles appropriately, but it was a rough month or so when I was getting titles and names mixed up.

To call a supervisor in for a meeting, an American PA would say, "John, please go to the screening room." Something bizarre to me is that, in Korea, when I'm looking a supervisor in the face or talking to him on the phone, I would never, ever say his name. I call him "supervisor (감독님)" and nothing else, as in "Supervisor, please go to the screening room (감독님, 시사실로 가세요)." When I refer to that person in a conversation and he's not around, I call him "John Supervisor (존 감독님)"-- yes, his name plus title. Like Mr. Smith, but more complicated. Imagine if, instead of just "mister," there were a plethora of other titles. That's Korea.

The rules and regulations for all these titles is confusing enough. To add formal and casual speech into the mix is just maddening. I used to just sigh in frustration through July and August because I just wanted to give up and spout off in English. I actually used to do that, but my English-speaking co-worker (two of them, actually) left the company. Those traitors, abandoning me.

The differentiations in speech and titles means that there's a sort of built-in caste system here in Korea (okay, there's no serfs, but you know what I mean!). As I understand it, visual effects (and animation) companies are the most casual, while big conglomerates are just staggering in their structure and strictness. The lowest on the totem pole tend to be the youngest, and the young ones that are high on the totem pole tend to be totally obnoxious. It's such a strange cultural difference that I never even thought about before I started working here, after which I was in work culture shock for about a month.

I feel like it's easier to get to know someone in the States because you're actually seeing their personality on a daily basis if you work together. Sure, they may be sugar-coating themselves and putting on their work veneer, but it's a light coating, like the dusting of powdered sugar on a doughnut. Koreans that work together can't really get to know each other, because there are titles and formal speech working against them. There is a shiny coating of politeness and respectability that is thickly layered over almost all Koreans in the workforce, shellacked into place through years of cultural expectation.

To counteract the formality and the stiffness, Koreans have come up with nights out among co-workers (hweshik, 회식). As I said before, it's a mandatory event that is akin to forcing an impatient four-year-old to sit through an opera. Sure, it's fun at times, but not being given a choice can rankle. I was a little bit pissed just for the principle of it, then realized I was being an idiot and cheered up (and drank up).

There are exceptions to these rules, of course. One of them being ... me. That's right. Though I am Korean, I am also American, and my Korean co-workers regard me with something akin to fear. I am allowed to be (and even expected to be) more facetious, more rambunctious, and more disrespectful that my peers. I suppose that I am mostly happy about that, because it lets me be me. My shellack isn't as thick as that of my equals, so I'm more myself than my co-workers are themselves. Co-workers tell me that my Korean is really good, which they would never tell to one of their Korean co-workers. They ask me questions about America, that great big mystery over the ocean. They ask me how to pronounce words. They generally just treat me a little bit differently. Some of the things that I've been asked or told:

How come your English is so good? (I replied, because I'm American.) Oh. How come your Korean's so good?

You're giving me a complex, your pronunciation is too good.

It's like you're a real American person!

Do you miss American food? Hot dogs, hamburgers?

How come Americans wear their shoes in the house? (I really don't know, and I don't get it.)

Who are you?? (An alien, here to steal your brain.)

- Automatic disrespect:

That's right. There's a flip side to this coin, the dark underbelly of Korean workplaces. If you will harken back to your Asian history, the Korean War was technically between 1950 and 1953. That's not quite sixty years ago. I applaud the ROK for its significant growth from a war-torn third-world country to a very developed, very wired democracy. That growth comes with a price, of course, and part of the price is the legacy of disrespect.

Old Korean people can be horrible. They can be pushy, loud, and terrorizing. There is an acceptance that if you're old, you deserve everything. It's an entitlement issue that is the norm here, and it just baffles me.

In Korea, this disrespect holds true in age and also in gender. This article from the Economist says that South Korean women make only 63% of what their male peers earn. Perhaps that figure has gotten better, but I doubt that it's changed very much. I see this attitude (one could call it discrimination if one were American) on a daily basis, as the youngest women at work are ordered around and spoken casually to and generally just not given the same amount of respect that their male counterparts receive. Okay, sure, women are sort of coddled, more so than they are in the States, but I'd rather have the respect and carry my own laptop bag.

Again, I am an exception to these rules. Though women that are the same age as me are spoken to casually and ordered to do random things that have nothing to do with their actual jobs, those same men speak formally to me and wouldn't dream of asking me to fetch them a coffee (probably because they can tell that I would snap one of their appendages off if they dared). I try to be an advocate for the people that have no voice at work, because they don't even air their grievances. They didn't even tell me that they had such issues until a few weeks ago, when they finally felt close enough to me to unload. So since they can't (or won't), I speak up on their behalf when I feel that something is wrong. I have a voice, unlike those wide-eyed newbies.

This means, perversely, that I am the bad cop. I'm always the bad cop in almost every situation, because I lay out ground rules and I actually stick to my guns. Koreans have this laxness about how much work they're willing to deal with, in quantity and quality. If a director asks for ten more shots, Koreans will chirp, "anything you want! No problem!" while I am grousing about receiving overages and adjusting the budget and working out a new schedule.

I think the supervisors regard me as a strange creature because I am not as typically passive-aggressive and people-pleasing as most Koreans (though I am much more people-pleasing than a lot of Americans). But I get away with it all simply because I'm a foreigner.

- Overtime, or lack thereof:

In the States, hours are tracked and scrutinized because overtime adds up to a LOT of money. In Korea, everyone (and I mean EVERYONE) receives a salary. They don't deal with any silly overtime.

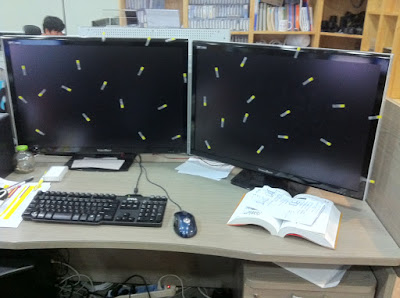

So, to compare: During "The Green Lantern," I stayed at work past midnight less than ten days throughout the project, which lasted a total of 13 months for me. During the movie that I am currently mired in, I have stayed at work past midnight about ten days in the month of September alone. I work on weekends, I work from home, I get phone calls on my cell, and because I'm in Korea, where everyone picks up their phones no matter where they are, I'm expected to pick up my phone without fail. Well, guess what? I hate talking on the phone, and I will willfully ignore you if I feel like it. I turn off my phone when I get home and I don't turn it on again until I wake up in the morning.

I have nothing against working; in fact, I love working. I don't mind staying late, I don't mind putting in the long hours. What I mind is looking at a project and seeing very clearly that those long hours could have been avoided with better planning.

Because time is literally money in the States, long hours aren't as brutal. Because Koreans use time to fix their lack of a detailed, hardcore schedule, long hours are expected and are the norm. I'm a big fan of pre-planning and executing the plan. I believe that a bad plan can be adjusted as the project trundles along. There is no fixing a non-existent plan. Maybe that's just my logic and my overly dominant left brain, but that's always been my attitude.

- Wink, wink, nudge, nudge:

I mentioned it briefly previously, but the way post-production is dealt with in Korea is very loose. Bids are a page long (if that) and basically just say "the work that you want us to do will cost X amount of money." American bids (at least for the bigger companies) are complex documents that include everything and anything that is relevant, broken down into the smallest denomination possible. They may even be overly detailed, but they are more accurate because a lot of thought and effort needs to be put into them in order to complete the bid.

In my past experience, if something changes, we used to stop working on whatever that asset or shot was until the budget was resolved. Sometimes, if the cost was negligible enough, we just did the work (rarely). If the change was substantial and would take more than a couple man days, an overage is calculated by re-bidding the asset or shot and charging the studio.

I miss those days.

In Korea, it's all about freebies. The director wants to add a herd of goats instead of the one goat that we bid for? Sure! The director wants to add FX water splashes to an entire scene that used to just be wire removals? Why not! The list just keeps on going. Koreans don't think it's weird to just do all this extra work, they think it's normal. It floored me the first time I realized that this was happening- it still shocks me, when I hear about a movie that's taken on extra work. Why, people, why?? Don't work for free, even if it's for your hero or your role model. Or especially if it's for a family member. Just don't do it. It never ends well.

- Personal property:

There are some instances of personal property issues in the States, sure. People write their names on their lunches in the company refrigerators. A few people label all their office supplies (I never did that- I mean, who's going to steal my stapler??). People are protective of their stuff, which I always thought was normal.

Today, I caught myself going to my co-worker's desk and snagging a snack. Yesterday, I went to a co-worker's desk to use a highlighter. I no longer think about it- I just go and take or use someone else's stuff. I never did that in the States unless it was someone that I knew really well.

Koreans are very fast to share (apparently, Americans don't learn as much about sharing in kindergarten as I thought). People share food, drink, office supplies, cars, everything. They will bring things to share, be it coffees or snacks or hand-held fans. I admit that there is a certain closeness that comes about because of all the sharing. Maybe sharing really is caring... Koreans are also quick to touch one another in a platonic way, though slow to touch in an intimate way. Even men are very touchy-feely, and it's not weird to see a guy sitting on another guy's lap. They're just being Korean.

I think the difference can be described as a pack mentality versus a loner mentality. Koreans don't like being alone, and are constantly communicating with or meeting with other people. I've been asked many, many times whether I'm okay living on my own (of course I am). If I'm walking out during lunchtime to run an errand by myself, people will stop me and make sure I'm not going to eat by myself. Americans are quick to make friends, but don't have as much of a problem being alone. Alone time is a good thing, at least on occasion. I think, though, that "alone time" can turn into "me time," which shows a sort of self-centered side to Americans (or LA people, maybe). Americans look out for themselves and protect number one, a concept that isn't part of the average Korean's mindset.

I see the pros and cons for both attitudes, and definitely think that going to either extreme is not healthy. That balance is hard to figure out, though I think that my time in Korea is helping me to see that there really is a balance to strike.

Being in Korea and discovering the other half of my cultural identity is an eye-opening experience which has made me realize why I never felt American enough back home. Of course, I don't feel Korean enough here, but again- I have a balance to find, and am trying to find it. I also have to figure out my future (or at least the year 2012) and am not really motivated to do so. Today, I just want to give my brain a rest. Tomorrow, I'll start picking through my options to see where I land.

I've been writing this post on and off all day long, and it's now past 10:30 at night. I'm at work, alternating between busyness and idleness, and am ready to go home for some sleep. I refuse to proofread this, I'm tired and rebellious.

The weather has gotten cold this week, as cold as winter in LA. I'm told by my co-workers that this weather is cool and autumnal, though I'm wearing a wool cardigan and shivering. It actually does feel like a distinctly different season, more so than it did in Albuquerque, my only previous experience with real seasons. I just want the leaves to change colors already!

I still have some work to do, so I'm going to get to it and then, hopefully, leave work before midnight. I have a feeling that this post will have a sequel, because I have the nagging sensation that I left some stuff out, but my mind is too bleary to think of it now. Yawn.